By Hoccas Siwel

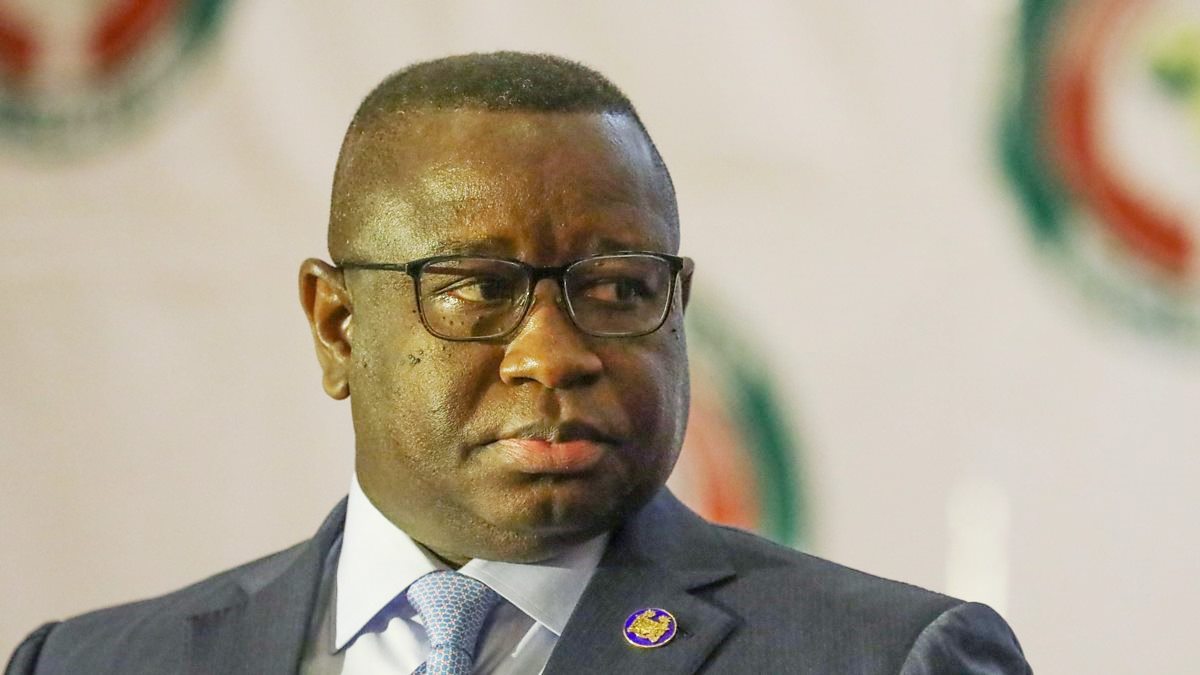

Is there a chance that our President would make it for a second term? I wouldn’t count on that as even top officials in the SLPP are in doubt based on what they consider his out of touch policies that don’t put food on the plates of the average man on the street. But considering recent regional occurrences in Guinea and Ivory Coast, and seeing that he still has to complete his first term, talk of a second is premature, though by trying he won’t be out of sync as there is even a bigger target at stake.

Going by recent election trends in Africa and the world, presidents are beginning to see their two term limits as hindrances to their developmental aspirations. No sooner than they started making real economic, political and social headways they have to risk it all during an election.

But why not take away this impediment like China has done with President Xi Jinping being made president for life? Closer to home we have Paul Kagame who many are calling a benevolent dictator. But Sierra Leone cannot boast of any president or aspirants of the ilk of these aforementioned champions of progress for their respective peoples and countries.

We are convinced that repetitive elections are important benchmarks for assessing the maturity of Africa’s electoral democracies. Yet the processes through which elections entrench a democratic culture remain understudied. Here an important mechanism called a democratic rupture – an infraction in the democratisation process during competitive elections that has the potential to cause a constitutional crisis, is factored in.

Recent happens around the continent have us worried that since Sierra Leone is a country that ‘falamakata’ (copies everything) that it would only be a matter of time before we start hearing their repeated calls here in Salone.

People wanted to make a comparison between the US presidential election and Sierra Leone, failing to see that one should be made closer to home.

The Third Term Drive (TTD) is slowly gaining ground with incumbent presidents calling for national referenda to extend their two term presidential limits. Taking their cues from Paul Kagame of Rwanda without justifying their calls to literally become presidents for life with real tangible proof of progress and or development, these men go against established norms even to civil conflicts or their brinks to hold on to power.

China has made communism hers hence you hear of “communism with Chinese characteristics.” Where do we have democracy with African characteristics in Africa? So if we haven’t owned democracy as ours but doing it as it’s done in the west, we will always be the laughingstock of world democracies.

Look at what happened to Alpha Conde in Guinea and Alassane Ouattara in Ivory Coast. There have been recent calls in Liberia for George Weah who is yet to complete a term to be allowed three.

While Americans have shown us that a second term is not a right or guarantee, here at home Africa is a continent with a strong incumbency advantage at the presidential level.

According to George M. Bob-Milliar and Jeffrey W. Paller in ‘Democratic Ruptures and Electoral Outcomes in Africa: Ghana’s 2016 Election’, between 1990 and 2009 there were only nine instances of an opposition candidate defeating a sitting incumbent; four of these cases were in founding elections, while three took place in Madagascar.

Incumbent parties are also more likely to lose support in open-seat polls, where an incumbent president is not contesting. This contributes to a context where defeating an incumbent president is a highly unlikely affair. The inability of opposition parties to defeat incumbents is a potential threat to a country’s broader democratisation process, as governing parties can consolidate economic, social, and political control over the citizenry. We see this as a clear manifestation of the president for life syndrome, which attempts to abandon have suffered major setbacks in Conde and Ouattara, and allowing Uganda, Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Chad and the like to have presidents for life.

According to The Conversation, after Ivorian president Alassane Ouattara (78) finally confirmed that he’ll seek a third term in office in October, within days of this Guinea’s ruling party asked President Alpha Conde (82) to seek a third term.

Those actions signaled that Africa is a long way from burying the ugly era of presidents for life. The period, which followed immediately after independence and lasted until the end of the 1990s, had a debilitating effect on stability, democracy and socioeconomic development on the continent.

In the last two decades the continent, through the African Union (AU), has developed relatively effective ways of putting a halt to unconstitutional changes of government in the form of coups d’etat. This policy effectively protects incumbent leaders. But the AU has yet to successfully tackle the problem of imperial presidencies.

This lack of action has triggered criticism that the organisation is a private club of incumbent leaders. Africa has more than its fair share of presidents who have stayed longer than they should have. Seven of the ten longest serving presidents in the world are in Africa. They include Cameroon’s Paul Biya, in power since 1982, and Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea, in power since 1979.

Their regimes are often characterised by instability, the absence of civil and political liberties as well as extensive patrimonialism and corruption.

Alpha Conde came to power in 2010 from the opposition ranks, following the first competitive elections in Guinean history after the death of Lansana Conte in 2008. Conte had come to power in a coup 24 years earlier.

A transitional government was established in 2010. This was followed by the adoption of a new constitution in 2010 and elections. Conde had been an ardent opponent of Conte. Notably, he opposed a 2003 constitutional amendment that allowed Conte to run for a third term.

After coming to power in 2010, Conde quickly consolidated his power through the hegemony of his party, Rally of the Guinean People, and won a second term in 2015. In 2019, his government announced that it would pursue the adoption of a new constitution. It deliberately aimed at bypassing a provision prohibiting amendments to the two term limit.

The opposition criticised the move as defying the spirit of the 2010 constitution against unlimited terms. Protests were held in the capital, Conakry, and other parts of the country, ever since October 2019.

They forced the postponement of the constitutional referendum, which was ultimately held on 31 March this year, and approved the new constitution. The constitution retained the two-term limit, but is silent on time already served before it came into force, enabling Conde to seek two more terms. He could potentially rule until 2032.

Protests continued despite COVID-19 restrictions, and several people were killed by security forces. We now know the outcome of the election, with Diallo under house arrest and supporters arrested and killed, and borders closed. With Conde’s stranglehold over the electoral management body, state resources, bureaucracy and security forces, and limits on opposition groups, the elections weren’t free and fair, which assured his victory.

However, there have been some notable examples of democratic changes in leadership in Africa due to term limit legislation. Most recent examples include in the Democratic Republic of Congo (2019), Sierra Leone (2018) and Liberia (2017). In all three countries, the elections were characterised by strong competition, and won by the opposition.

But many other presidents have tampered with their countries’ constitutions to extend their stay in power. The list includes Togo (2002), Gabon (2003), and most recently Ivory Coast and Guinea. Imagine Ouattara has done exactly what Laurent Gbagbo was removed and locked up for, albeit with the tenacity of adept politricster unlike Gbagbo who did his after losing the election.

The latest abuses should show that there’s still a way to go to stamp out this practice. A number of practical steps should be taken urgently.

Firstly, loopholes need to be plugged. One is to ensure that, when new constitutions are adopted, they are specific about the fact that terms already served in office still count. The Gambia’s draft constitution sets a model for the continent. It not only establishes two term limits, but also specifically counts terms served prior to its adoption.

In addition, the African Union needs to revive efforts to impose a continent-wide two term limit on presidents on the continent. A proposed provision in the draft African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance, which aimed to do so in 2007, was scrapped after Uganda led opposition to its adoption. Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni had already removed the two term limit from the country’s constitution in 2005.

Similarly, an effort by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) to establish a two-term limit was shelved in 2015 due to opposition from The Gambia, then under dictator Yahya Jammeh, and Togo, whose constitutions contained no term limits.

The African Union, ECOWAS and other sub-regional organisations need to reignite efforts to build a specific policy of two terms. Only such a continental ban could preclude domestic legal manoeuvres and bury the ghost of life presidents. Once approved, the African Union would be able to sanction, and even expel, countries that violate the term limits.

The organisations would be pushing at an open door. Only five countries with presidential systems on the continent do not have term limits. They are Eritrea, Somalia, Cameroon, South Sudan and Djibouti. Most of the countries that had removed term limits have since reinstated them. Examples include Uganda, whose parliament reinstated presidential term limits in 2017. But Museveni, who has been in power for 34 years, is still running again.

Togo did so last year, although the incumbent, President Faure Gnassingbe, who has been in power since 2005, is not precluded from contesting future elections. He could potentially be in power until 2030. Without a concerted effort to establish a continental two-term policy, Africa may be bound to live with the spectre of presidents for life.

The president is being seen as out of touch with the real needs of the people. While he is making policies and other moves to meet international benchmarks, the reality on the ground is appalling especially during this Covid 19 era of closed businesses hence high unemployment. There are doubts that he won’t make it past the first, and that it would take great machination to get a second.

While he has made no mention of wanting a third term or asking for a referendum to change the constitution (he may or may not go past 2023); but should he, what would Sierra Leoneans do seeing what happened in Guinea and Ivory Coast?